The Sanders home in Penfield, GA where Cynthia Sanders raised 13 children of her own and boarded students of the fledgling University. “She hath done what she could,” (Mark 14:8) is inscribed on the grave of Cynthia Holiday Sanders a 19th century Baptist pioneer buried at Penfield, Georgia. COURTESY/Charles Jones

The 19th century saw a transformation of the role of women in Baptist life. The denomination was changing, growing, and developing collective ways of supporting local churches, missions, and education. The role of women was changing to reflect the changing times. Given the living conditions and social norms of the day it was not easy, but they pressed on and did what they could to advance the kingdom.

After the second U.S. census in 1800, it was determined that the average life expectancy in the American south was between 35 and 40. The death rate of infants and children was high. Among childbearing women, one in 64 births resulted in the death of the mother and on average women bore 8 children in their lifetime.

Life was difficult at best. Disease, infections, poor nutrition, and poor sanitation were more likely to contribute to death than old age. If a person survived to the age of 40 there was a good chance a person could live to old age. In the last quarter of the century advances were being made in health and sanitation, but by the end of the century in 1900 life expectancy was still only 45. Educational advancements and opportunities for both men and women increased. Rural counties developed “field schools” which provided education up to the seventh grade. Within a decade of the establishment of (all male) Mercer University, Baptist schools for women including “Penfield Female Seminary” and “Monroe Female University” were being established across Georgia. In addition to providing expanded educational opportunities for women, these schools offered training and employment opportunities outside the traditional roles of homemaking.

During this time Baptist women of the south were more likely to be living in rural sections of the states than in urban centers. Over the course of the century more Baptists migrated to urban areas. Early women’s leadership came primarily from urban areas--county seat towns, mill villages, and cities.

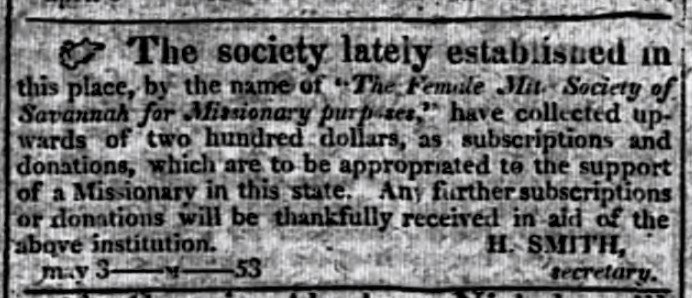

The earliest recorded Baptist women’s missionary societies in Georgia were organized in 1817. They were the Savannah and the Sunbury Female Mite/Cent Societies. Typically, these societies were composed of women from multiple churches. Members paid dues which were forwarded to support missions. In its first two years the Sunbury Female Society sent over $300.00 to support missions.

When the Georgia Baptist Convention was organized in 1822 its messengers were composed of members representing both associations and missionary societies across Georgia. (Individual churches did not elect messengers until 1877). Women’s missionary societies had a vote but were represented by a man at the Convention. Through the early 20th century, Baptist women’s financial contributions to missions were reported separately to receive credit for their work and possibly as a means of lobbying for a larger voice in Baptist life.

The second area of support through these societies was prayer. When the early societies met, they might read a missionary report or letter published in The Christian Index or secular newspapers. But as they prayed, the prayer was not restricted to missions. It was also for their local churches, associations, the state, nation, and the world. In this context they prayed for revival.

The earliest women’s missionary societies were organized during the era of the Second Great Awakening (ca. 1787-1830s). These were powerful revivals that ebbed and flowed across America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Probably the greatest revival to sweep across Georgia was the Great Revival of 1827-1828. During that revival Georgia Baptists doubled in size in two years.

Adiel Sherwood, who was preaching when the revival broke out at an associational camp meeting, credited the prayers of women with lighting the flames of revival. “I believe the great revival had its origin in a ladies’ prayer-meeting which had been faithfully observed by a few members of the Eatonton Church.”

His sister, Charlotte Sherwood Fleming, organized and promoted these prayer meetings. Charlotte’s sister-in-law later wrote of her role in those prayer meetings: “How many during the great revival of 1827, had cause to bless God for sending her as an angel of mercy to arouse them to the vast concern of their souls!”

Charlotte Sherwood Fleming was a minister’s wife and an educator who died at age 51. She left no children, but she did leave a powerful legacy of a praying woman!

Early women’s missionary societies, scattered across Georgia, began to be recognized for their financial support of missions and their spiritual support through prayer. This was the beginning of a new and growing voice of women in Baptist life.

As Baptists established schools, women began to support the work of Baptist higher education. Most of these schools including Madison Female Academy and later Shorter College included women on the faculty. Women, in missionary societies, promoted offerings and supported the work through prayer.

One woman who was an educational trailblazer was Cynthia Holiday Sanders (1804-1887), the wife of the first President of Mercer University. In addition to raising 13 children of her own, she and her husband boarded students in their home. She helped cook for the student body and in other ways took care of these young men, many of whom were barely in their teens.

She was affectionately remembered as the “Mother of Mercer.” But her work was not confined to the kitchen. She was also a businesswoman. One of her daughters-in-law wrote in a 1927 biographical sketch, “As a financier and businesswoman she had few equals among women of her day and generation. Her husband and the Trustees often invited her to sit in the councils and deliberations.”

At a time when women could not serve as trustees of Baptist organizations, she paved the way for future women by her sound wisdom and advice. At her request, the epitaph on her tombstone was Mark 14:8 “She hath done what she could” . . . and she did it well!

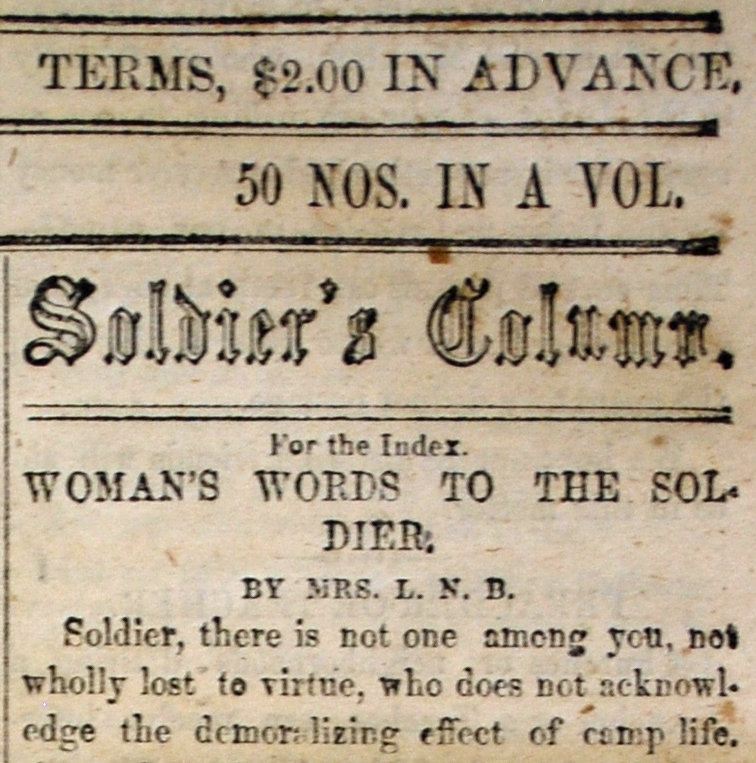

Women’s voices began to emerge on the pages of The Christian Index and tracts published by the Georgia Baptist Bible and Colporteur Society during the 1860’s. The Index began a feature called the “Ladies Department” in early 1861 after Samuel Boykin became the owner/editor of the Index. One of the writers was his wife Laura Nisbet Boykin.

The Georgia Baptist Bible and Colporteur Society was founded in 1858. It sold and distributed Bibles and Christian literature. At the advent of the Civil War, it began producing tracts for soldiers. Their enlistment of women writers allowed women’s voices to take another stride forward. This was the first-time women were specifically asked to address a male audience.

Why did this happen? One of the most effective gospel tracts of the Civil War was titled, “A Mother’s Parting Words to her Soldier Boy.” The impact of this tract by Frances Blake Brockenbrough, published by a North Carolina tract society undoubtedly opened the door for more women writers including those from Georgia.

Three Georgia Baptist women--Mrs. Laura Nisbet Boykin, Mrs. Louisa Born Haygood (wife of the General Agent of the Colporteur Society), and Mrs. Mary M. McCrimmon--wrote tracts for the Colporteur Society: “The Seed” by Mrs. Haygood, “Women’s Words-To the Soldiers” by Mrs. Boykin, “The Mourner” and “Letter to a Sick Soldier” by Mrs. McCrimmon.

By mid-nineteenth century Baptist standards this was significant milestone which foreshadowed an increasingly visible role for Baptist women writers in the decades to come. They left a legacy of a fresh voice in Georgia Baptist life and paved the way for many more women writers who still follow in their footsteps today.

By the later decades of the 19th century women across America, especially in urban areas were beginning to organize for temperance, women’s suffrage, and other causes. It was during this season that Women’s Baptist Missionary Unions began to organize across the country. This was an effort to organize local missionary societies to cooperate on state and national levels.

In Georgia, early leadership primarily came from urban centers, especially Atlanta. Most of these were women from wealthy families. They had more leisure time, lived in closer proximity to one another to meet on a regular basis, and had disposable income that could be channeled into support of missions and the temperance cause.

The early Georgia organization struggled to find a unified voice until it found a specific purpose to rally around. Where the Baptist men of Georgia had failed, the women would prevail. The need was an orphanage. Following the Civil War, the first Baptist orphanage was established for the children orphaned by the war. This orphanage operated from 1874-1884 and closed due to lack of financial support. Its properties and resources were sold, debts were liquidated, and the remaining balance of funds were given to Mercer University.

The failure of the orphanage was not due to lack of need, it was lack of resources. Led by the women of Atlanta, Georgia Baptist women rallied around this need in 1888 opening the doors of a new orphanage in 1890. The orphanage became a key unifying factor around which women across the state would unite. The board of the new orphanage was made up entirely of women. This was the only Baptist institution in Georgia where women had a recognized vote. Because of the successful operation of the orphanage, in 1898 the Georgia Baptist Convention asked to share ownership. When the charter of the orphanage was changed it included the provision that 14 out of 25 trustees must be women.

This brief overview cannot begin to cover all the women who were pioneers in advancing the kingdom in Georgia. Many of these women’s accomplishments have been overlooked or forgotten. Yet the story to be told is that given the difficult circumstances and obstacles which confronted them, these women served faithfully, prayed fervently, and persevered fearlessly.

Cynthia Sanders’ epitaph states, “She hath done what she could.” This verse was Jesus’ response to the naysayers who chastised a woman who had broken an alabaster box of precious ointment anointing his head. Jesus recognized what she had done as a selfless extravagant act of love which no one had the right to deny her. Jesus was saying, let her serve me with what she has; she has given her best.

Furthermore, Jesus said she would be remembered for what she had done. Many 19th century Baptist women and those who continue to follow Jesus today are still serving, praying, preserving, and giving as extravagant acts of love. They are giving their best to the Master following a trail that others blazed before them. They should not be denied the opportunity to serve Jesus, and they should be remembered for what they have done!